When those interested in animal health began talking about taking a more holistic approach, initially I was quite excited. I felt this way because I expected their approach to be, well, holistic. But as often happens, holistic has multiple meanings. I ascribed to the definition of holistic medicine put forth by Oxford Dictionaries: In medicine holistic means “Characterized by the treatment of the whole person, taking into account mental and social factors, rather than just the physical symptoms of the disease”. But very soon I discovered that many human and animal care professionals and members of the public preferred the second dictionary.com’s definition instead: “identifying with principles of holism in a system of therapeutics, especially one considered outside the mainstream of scientific medicine, as naturopathy or chiropractic, and often involving nutritional measures.”

The second definition created a medical oxymoron—a system that treated problems using treatments that were developed based on awareness of the whole individual in that environment. On the upside , this approach fit nicely with the scientific method and enabled supporters of some of these treatments to validate their products. On the downside, it removed the “whole” from holistic.

While this transformation was occurring in the medical and behavioral sciences, those in the biological sciences were becoming more interested in taking an ecological view. Coined by German biologist Ernst Haeckel in 1869, the term ecology arose from Greek word oikos which means “house”. It refers to the study of the interactions of all those dwelling in an environment. In some ways ecology takes the original all-inclusive approach to the individual mind-body and applies it to that individual and everything that individual interacts with in that environment.

What does an ecological orientation potentially mean for animal health? One subdivision of ecology, medical ecology, considers the body’s microscopic residents—bacteria, parasites, fungi, viruses etc.—as part of the body’s ecology. Admittedly this is a limited view compared to the all-inclusive biological one. On the other hand, it’s superior to ignoring the behavior of these trillions of residents that can and do affect the workings of the entire human and non-human animal body because they comprise most of its mass. In keeping with the problem-oriented approach, how the composition of the micro-population manifests in physical or behavioral disease gains the lion’s share of the funding and research. In some areas—such as the use of natural or synthetic probiotics and fecal transplants—human medicine embraced this more quickly than veterinary medicine. This occurred even though preliminary studies on both were done on laboratory animals. While fecal transplants have yet to become common in veterinary medicine, the results of preliminary studies of their use to treat chronic diarrheas has been encouraging.

To some extent the rise of an ecological approach was inevitable given one unintended consequence of conventional and pseudo-holistic problem-oriented approaches. You can’t keep treating living people and animals composed of micro-systems that constantly interact with multiple larger systems as isolated problems forever. Although that approach may seem statistically sound, nature doesn’t work that way. As we as a society became to accustomed to readily available treatments for problems that ailed or might ail us and our animals, we started to cut corners relative to multi-systemic cleanliness, food consumption, fresh air, clean water, and exercise. We became more remote from nature and in the process became more remote from ourselves and our animals.

Another unfortunate consequence of our choice to deny the crucial role these micro-systemic organisms played in our and other animals’ normal physical and behavioral identity was that we started to perceive them all as pathogens. We became clean freaks. Puppies eating their own stool—a not uncommon behavior during the first year of life—disgusted us beyond words. The thought of any kind of external parasite on or in the body or anywhere in the environment freaked us out even more and we immediately wanted to destroy it. Whether we chose holistic or conventional treatments and preventives, we medicated ourselves and them.

In the process of doing so, however, it appears that we’ve traded in problems caused by what we perceived as infections by alien predatory viruses, bacteria, and parasites hellbent on our destruction and replaced them with diseases like asthma, allergies and all those others related to a breakdown of the immune response. This shift, first noticed 1958, gave rise to the Hygiene Hypothesis. Being only human though, we opted for denial. But then these diseases began to pile up with precious few cures in sight, and then antibiotic and now fungicidal resistance reared reared their ugly heads. Once that happened, it became clear to more folks that a more comprehensive ecological mindset was needed.

But that isn’t as easy as it may seem. For a long time studies have demonstrate how wild animals self-medicate for various reasons, including parasite control. Studies of domestic sheep also demonstrated that they’ll do the same if given the opportunity. The key word here is “controlled”. The natural treatments don’t result in a zero-tolerance approach toward parasites. Instead, they maintain an optimal baseline population that benefits host and parasite. Would we be willing to accept that for ourselves, our kids, and our animals? More importantly, could we even implement such a program given the increased size of the immune-compromised population in developed nations?

Current circumstances may force us to test this approach on an especially vulnerable animal population: members of endangered species raised in captivity and released in the wild. Because these animals are so rare and vulnerable, conventional wisdom has maintained that they be raised in parasite-free environments. Additionally they’re treated with anti-parasitic medications before their release. However, researchers Hamish Spencer and Marlene Zuk note that exposure to parasites early in life improves resistance to those same parasites later and also enhances function of the immune response in general.

But this isn’t without its risks. In Western society we’ve created a medical system that, if one can afford it, is on-demand and problem-specific regardless of the treatment and preventive approach. Neither healthcare providers nor consumers give much, if any, thought to the effects this approach may have on the inextricably entwined internal and external ecosystems. The same is even more true regarding the rarefied environment in which captive endangered species are raised. Were we to expose this sometimes fragile population to certain parasites, some of them almost certainly would die. Are we ready to face the loss of some to ensure the survival of more, including an entire species?

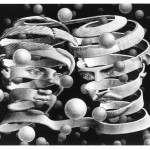

Making the shift from problem-oriented thinking to a more comprehensive and realistic if less convenient ecological approach won’t be easy. It’s the kind of transition that makes me sympathize with the humans in this image by that master of illusion, M.C. Escher. Add how much we as a society currently have invested the more limited way of thinking and controlling fall-out it’s created for human and animal well-being , and the possibility of any risks involved in any shift, it will require courage and commitment.

Given all that, it may well be that it won’t be tried until every problem-oriented approach has failed and there’s nothing left to lose.

When those interested in animal health began talking about taking a more holistic approach, initially I was quite excited. I felt this way because I expected their approach to be, well, holistic. But as often happens, holistic has multiple meanings. I ascribed to the definition of holistic medicine put forth by Oxford Dictionaries: In medicine holistic means “Characterized by the treatment of the whole person, taking into account mental and social factors, rather than just the physical symptoms of the disease”. But very soon I discovered that many human and animal care professionals and members of the public preferred the second dictionary.com’s definition instead: “identifying with principles of holism in a system of therapeutics, especially one considered outside the mainstream of scientific medicine, as naturopathy or chiropractic, and often involving nutritional measures.”

The second definition created a medical oxymoron—a system that treated problems using treatments that were developed based on awareness of the whole individual in that environment. On the upside , this approach fit nicely with the scientific method and enabled supporters of some of these treatments to validate their products. On the downside, it removed the “whole” from holistic.

While this transformation was occurring in the medical and behavioral sciences, those in the biological sciences were becoming more interested in taking an ecological view. Coined by German biologist Ernst Haeckel in 1869, the term ecology arose from Greek word oikos which means “house”. It refers to the study of the interactions of all those dwelling in an environment. In some ways ecology takes the original all-inclusive approach to the individual mind-body and applies it to that individual and everything that individual interacts with in that environment.

What does an ecological orientation potentially mean for animal health? One subdivision of ecology, medical ecology, considers the body’s microscopic residents—bacteria, parasites, fungi, viruses etc.—as part of the body’s ecology. Admittedly this is a limited view compared to the all-inclusive biological one. On the other hand, it’s superior to ignoring the behavior of these trillions of residents that can and do affect the workings of the entire human and non-human animal body because they comprise most of its mass. In keeping with the problem-oriented approach, how the composition of the micro-population manifests in physical or behavioral disease gains the lion’s share of the funding and research. In some areas—such as the use of natural or synthetic probiotics and fecal transplants—human medicine embraced this more quickly than veterinary medicine. This occurred even though preliminary studies on both were done on laboratory animals. While fecal transplants have yet to become common in veterinary medicine, the results of preliminary studies of their use to treat chronic diarrheas has been encouraging.

To some extent the rise of an ecological approach was inevitable given one unintended consequence of conventional and pseudo-holistic problem-oriented approaches. You can’t keep treating living people and animals composed of micro-systems that constantly interact with multiple larger systems as isolated problems forever. Although that approach may seem statistically sound, nature doesn’t work that way. As we as a society became to accustomed to readily available treatments for problems that ailed or might ail us and our animals, we started to cut corners relative to multi-systemic cleanliness, food consumption, fresh air, clean water, and exercise. We became more remote from nature and in the process became more remote from ourselves and our animals.

Another unfortunate consequence of our choice to deny the crucial role these micro-systemic organisms played in our and other animals’ normal physical and behavioral identity was that we started to perceive them all as pathogens. We became clean freaks. Puppies eating their own stool—a not uncommon behavior during the first year of life—disgusted us beyond words. The thought of any kind of external parasite on or in the body or anywhere in the environment freaked us out even more and we immediately wanted to destroy it. Whether we chose holistic or conventional treatments and preventives, we medicated ourselves and them.

In the process of doing so, however, it appears that we’ve traded in problems caused by what we perceived as infections by alien predatory viruses, bacteria, and parasites hellbent on our destruction and replaced them with diseases like asthma, allergies and all those others related to a breakdown of the immune response. This shift, first noticed 1958, gave rise to the Hygiene Hypothesis. Being only human though, we opted for denial. But then these diseases began to pile up with precious few cures in sight, and then antibiotic and now fungicidal resistance reared reared their ugly heads. Once that happened, it became clear to more folks that a more comprehensive ecological mindset was needed.

But that isn’t as easy as it may seem. For a long time studies have demonstrate how wild animals self-medicate for various reasons, including parasite control. Studies of domestic sheep also demonstrated that they’ll do the same if given the opportunity. The key word here is “controlled”. The natural treatments don’t result in a zero-tolerance approach toward parasites. Instead, they maintain an optimal baseline population that benefits host and parasite. Would we be willing to accept that for ourselves, our kids, and our animals? More importantly, could we even implement such a program given the increased size of the immune-compromised population in developed nations?

Current circumstances may force us to test this approach on an especially vulnerable animal population: members of endangered species raised in captivity and released in the wild. Because these animals are so rare and vulnerable, conventional wisdom has maintained that they be raised in parasite-free environments. Additionally they’re treated with anti-parasitic medications before their release. However, researchers Hamish Spencer and Marlene Zuk note that exposure to parasites early in life improves resistance to those same parasites later and also enhances function of the immune response in general.

But this isn’t without its risks. In Western society we’ve created a medical system that, if one can afford it, is on-demand and problem-specific regardless of the treatment and preventive approach. Neither healthcare providers nor consumers give much, if any, thought to the effects this approach may have on the inextricably entwined internal and external ecosystems. The same is even more true regarding the rarefied environment in which captive endangered species are raised. Were we to expose this sometimes fragile population to certain parasites, some of them almost certainly would die. Are we ready to face the loss of some to ensure the survival of more, including an entire species?

Making the shift from problem-oriented thinking to a more comprehensive and realistic if less convenient ecological approach won’t be easy. It’s the kind of transition that makes me sympathize with the humans in this image by that master of illusion, M.C. Escher. Add how much we as a society currently have invested the more limited way of thinking and controlling fall-out it’s created for human and animal well-being , and the possibility of any risks involved in any shift, it will require courage and commitment.

Given all that, it may well be that it won’t be tried until every problem-oriented approach has failed and there’s nothing left to lose.