Although companion animal spay and neuter history has ancient roots, its contemporary incarnations include an intriguing mystery. In addition to getting one’s genes into the gene pool, limiting the reproduction of perceived competitors has played a central role in species’s survival for eons. However, this also has led to a lot of irrational human behavior over the years, an effect that understanding the biological basics lessens.

Although companion animal spay and neuter history has ancient roots, its contemporary incarnations include an intriguing mystery. In addition to getting one’s genes into the gene pool, limiting the reproduction of perceived competitors has played a central role in species’s survival for eons. However, this also has led to a lot of irrational human behavior over the years, an effect that understanding the biological basics lessens.

Basic One: In species that reproduce heterosexually, sexually mature males produce large numbers of low-energy sperm on a daily basis.

Basic Two: During a limited period of their lives, sexually mature females produce a limited number of high-energy eggs that are only fertile during a brief period of time.

Basic Three: Therefore, males can father a lot more offspring over their lifetimes than females can give birth to.

Basic Four: This makes females the scarcer resource.

These fundamental biological differences result in different behaviors. For example, even if the species male-female ratio is roughly 1:1 and males possess a renewable, low-energy source of large numbers sperm, nothing guarantees a willing female for every male. On the country, it costs females so much more energy to produce eggs and support pregnancy and lactation, it pays females to select males with qualities that will ensure their and their offspring’s success. Consequently, on average only about 50% of the males will reproduce. This leads males of multiple species to engage in high-energy activities to eliminate male competition and impress females. This also leads to the different male physiology that support these behaviors.

However, males belonging to social species who overcome the competition using the least amount of energy prove themselves more fit than those who must severely injure or even kill their competitors. In nature’s world, nobody wins a fight; the winner merely loses the least. Because breeding seasons are short and protecting the group and its resources is a year-round job, overly aggressive males are a liability. Even if they succeed in destroying the competition, that’s no guarantee that any female will accept them. And when these males sustain injuries as they excessively maim or kill competing members in their own group, this makes the entire group more vulnerable.

Historically it’s unclear how human learned to castrate other males. Because males of many species expose their external genitalia to signal submission, it’s possible that humans would notice that some male animals would bite off their competitors’ genitalia in a fit of rage. And perhaps occasionally one of those mutilated animals survived long enough for curious humans to notice how much more tractable these animals were.

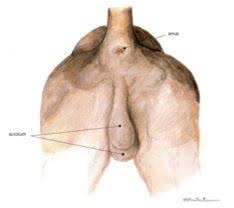

Canine Testicles

Via trial-and-error, castration eventually became a way to control the reproduction and behavior of males perceived as threats for some reason. However, initially that (very primitive!) surgery removed the other’s testicles and penis. Eventually though, humans learned they could retain the reproductive and behavioral benefits and lose the physical problems by removing only the testicles and leaving the penis intact. Early documentation describes the role castration played in the control of captured human male enemies who were then enslaved.

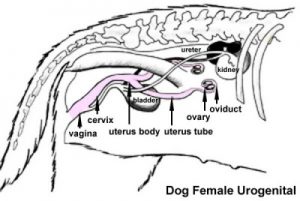

During this same period, observant humans undoubtedly also realized that relieving females of their reproductive organs wasn’t cost-effective. Unlike  male organs that were easily accessible thanks to their location outside the body wall, removing female ovaries and uteri required much more surgical skill. Death due to blood loss, accidental injury to or removal of vital organs, and infections surely were common. Long recovery times and side-effects that limited any survivors’ ability to work also would negate the goal of this kind of surgical control. Additionally, intact human and nonhuman animal females were more valuable as breeders and surrogate mothers.

male organs that were easily accessible thanks to their location outside the body wall, removing female ovaries and uteri required much more surgical skill. Death due to blood loss, accidental injury to or removal of vital organs, and infections surely were common. Long recovery times and side-effects that limited any survivors’ ability to work also would negate the goal of this kind of surgical control. Additionally, intact human and nonhuman animal females were more valuable as breeders and surrogate mothers.

It also seems reasonable that the ubiquitous wild dogs who hung around human towns and villages where they ate human garbage and waste would make good subjects to hone the surgeons’ skills. Although slaves’ lives may have carried little value compared to that of their captors and free humans, they did have a higher value than dogs.

Thus we can say that historically, commonsense mandated that castrating male animals was the most cost-effective way to control their behavior and limit their reproduction. That’s the (very brief) history. Now comes the mystery of companion animal spaying and neutering…

After thousands of years castrating male animals to control animal populations and soften male behavior, why the push for surgical sterilization of the US female pet dog population by the veterinary and humane communities in the post-WWII era?

Science historian James Burke offers insights about war that suggest how this may have happened. Science historians are a lot like ethologists in that they look at events in context instead of as isolated occurrences. In his discussion of the effects of war, Burke’s research revealed that wars provide excellent opportunities for surgeons to develop new skills. This occurs because often the facilities needed to perform accepted surgeries and the oversight that would prevent trying new ones don’t exist in war zones. Logic also says that many war-related surgeries would involve trauma to the internal organs of male and female soldiers and civilians. When the numbers of those with human medical technical skills were limited, it also seems reasonable that veterinarians might volunteer or be volunteered to fill the void.

Regardless of the specific reasons, a surge of surgery on women’s reproductive organs began after the war. US veterinary medicine, and especially pet animal practice, coincidentally opted to pattern itself after human medicine during this same period. So just as the number of hysterectomies in women increased dramatically during this period, so did the number of female dogs being spayed…

Except that unlike in human medicine where these surgeries were done for what were considered viable medical reasons at the time, veterinarians did it primarily for population control. Moreover, the primary emphasis was on spaying females. But even back then some in veterinary medicine questioned this approach. Among these were all those food/farm animal veterinarians who knew castration was the more logical option. As more women began joining the profession, they questioned it too. But whereas food animal practitioners’ objections was driven by knowledge, sexual politics contributed to the female response. I can say this because I was one of those females. As in, “Why are we only spaying females? We should be neutering males, too!” True, we could drag out the science to legitimize our views. But at heart this was a political issue. Instead of seeking the safest and most cost-effective form of canine population control, i.e. castration, we wanted to remove all canine testicles and ovaries and uteri to make everything “equal”. Simultaneously cat castration remained a constant and spaying was added later. Go figure. Although that probably had more to do with the stench of tom cat urine. Nobody cared much when cats stayed outdoors. But when they became full-time housepets and used litter boxes, that was a different story.

So began the somewhat bizarre gonadal wars that continue today. In keeping with the American marketing spirit that says that if something is good, then doing more of it faster and sooner is better, one volley took the form of spaying and neutering dogs faster and earlier. Including young puppies. Needless to say, these approaches generated a backlash from folks who didn’t want any dog spayed or neutered, or only certain dogs (usually mixed breeds) , or only if absolutely necessary for medical reasons. In the feline realm, these reactions existed but never quite gained the fervor of those in the canine realm.

As if all this weren’t messy enough to foil attempts to introduce reason into the process, the increased marketing of companion animals as symbols of human concerns did what symbolism always does. It made meaningful discussion of spay and neuter extremely difficult if not impossible. People who perceived their dogs symbolically used the words “spay” and “neuter”, but they weren’t talking about what benefited the dog, breed, or species. They were talking about what approach would support their personal beliefs regarding human reproduction and population control. Or abortion and free choice. Or maybe something else entirely. Is it any wonder these conversations weren’t—and aren’t—very productive?

But take heart. Despite the fact that social media may create the illusion that control over the reproductive organs of human and other animals is a contemporary social, moral, cultural, religious, political and/or scientific problem, it isn’t. It’s just today’s variation on an ancient animal theme of other-control that arose in an era when H. sapiens was barely a blip on the Cenozoic horizon.

Basic One: In species that reproduce heterosexually, sexually mature males produce large numbers of low-energy sperm on a daily basis.

Basic Two: During a limited period of their lives, sexually mature females produce a limited number of high-energy eggs that are only fertile during a brief period of time.

Basic Three: Therefore, males can father a lot more offspring over their lifetimes than females can give birth to.

Basic Four: This makes females the scarcer resource.

These fundamental biological differences result in different behaviors. For example, even if the species male-female ratio is roughly 1:1 and males possess a renewable, low-energy source of large numbers sperm, nothing guarantees a willing female for every male. On the country, it costs females so much more energy to produce eggs and support pregnancy and lactation, it pays females to select males with qualities that will ensure their and their offspring’s success. Consequently, on average only about 50% of the males will reproduce. This leads males of multiple species to engage in high-energy activities to eliminate male competition and impress females. This also leads to the different male physiology that support these behaviors.

However, males belonging to social species who overcome the competition using the least amount of energy prove themselves more fit than those who must severely injure or even kill their competitors. In nature’s world, nobody wins a fight; the winner merely loses the least. Because breeding seasons are short and protecting the group and its resources is a year-round job, overly aggressive males are a liability. Even if they succeed in destroying the competition, that’s no guarantee that any female will accept them. And when these males sustain injuries as they excessively maim or kill competing members in their own group, this makes the entire group more vulnerable.

Historically it’s unclear how human learned to castrate other males. Because males of many species expose their external genitalia to signal submission, it’s possible that humans would notice that some male animals would bite off their competitors’ genitalia in a fit of rage. And perhaps occasionally one of those mutilated animals survived long enough for curious humans to notice how much more tractable these animals were.

Canine Testicles

Via trial-and-error, castration eventually became a way to control the reproduction and behavior of males perceived as threats for some reason. However, initially that (very primitive!) surgery removed the other’s testicles and penis. Eventually though, humans learned they could retain the reproductive and behavioral benefits and lose the physical problems by removing only the testicles and leaving the penis intact. Early documentation describes the role castration played in the control of captured human male enemies who were then enslaved.

During this same period, observant humans undoubtedly also realized that relieving females of their reproductive organs wasn’t cost-effective. Unlike male organs that were easily accessible thanks to their location outside the body wall, removing female ovaries and uteri required much more surgical skill. Death due to blood loss, accidental injury to or removal of vital organs, and infections surely were common. Long recovery times and side-effects that limited any survivors’ ability to work also would negate the goal of this kind of surgical control. Additionally, intact human and nonhuman animal females were more valuable as breeders and surrogate mothers.

male organs that were easily accessible thanks to their location outside the body wall, removing female ovaries and uteri required much more surgical skill. Death due to blood loss, accidental injury to or removal of vital organs, and infections surely were common. Long recovery times and side-effects that limited any survivors’ ability to work also would negate the goal of this kind of surgical control. Additionally, intact human and nonhuman animal females were more valuable as breeders and surrogate mothers.

It also seems reasonable that the ubiquitous wild dogs who hung around human towns and villages where they ate human garbage and waste would make good subjects to hone the surgeons’ skills. Although slaves’ lives may have carried little value compared to that of their captors and free humans, they did have a higher value than dogs.

Thus we can say that historically, commonsense mandated that castrating male animals was the most cost-effective way to control their behavior and limit their reproduction. That’s the (very brief) history. Now comes the mystery of companion animal spaying and neutering…

After thousands of years castrating male animals to control animal populations and soften male behavior, why the push for surgical sterilization of the US female pet dog population by the veterinary and humane communities in the post-WWII era?

Science historian James Burke offers insights about war that suggest how this may have happened. Science historians are a lot like ethologists in that they look at events in context instead of as isolated occurrences. In his discussion of the effects of war, Burke’s research revealed that wars provide excellent opportunities for surgeons to develop new skills. This occurs because often the facilities needed to perform accepted surgeries and the oversight that would prevent trying new ones don’t exist in war zones. Logic also says that many war-related surgeries would involve trauma to the internal organs of male and female soldiers and civilians. When the numbers of those with human medical technical skills were limited, it also seems reasonable that veterinarians might volunteer or be volunteered to fill the void.

Regardless of the specific reasons, a surge of surgery on women’s reproductive organs began after the war. US veterinary medicine, and especially pet animal practice, coincidentally opted to pattern itself after human medicine during this same period. So just as the number of hysterectomies in women increased dramatically during this period, so did the number of female dogs being spayed…

Except that unlike in human medicine where these surgeries were done for what were considered viable medical reasons at the time, veterinarians did it primarily for population control. Moreover, the primary emphasis was on spaying females. But even back then some in veterinary medicine questioned this approach. Among these were all those food/farm animal veterinarians who knew castration was the more logical option. As more women began joining the profession, they questioned it too. But whereas food animal practitioners’ objections was driven by knowledge, sexual politics contributed to the female response. I can say this because I was one of those females. As in, “Why are we only spaying females? We should be neutering males, too!” True, we could drag out the science to legitimize our views. But at heart this was a political issue. Instead of seeking the safest and most cost-effective form of canine population control, i.e. castration, we wanted to remove all canine testicles and ovaries and uteri to make everything “equal”. Simultaneously cat castration remained a constant and spaying was added later. Go figure. Although that probably had more to do with the stench of tom cat urine. Nobody cared much when cats stayed outdoors. But when they became full-time housepets and used litter boxes, that was a different story.

So began the somewhat bizarre gonadal wars that continue today. In keeping with the American marketing spirit that says that if something is good, then doing more of it faster and sooner is better, one volley took the form of spaying and neutering dogs faster and earlier. Including young puppies. Needless to say, these approaches generated a backlash from folks who didn’t want any dog spayed or neutered, or only certain dogs (usually mixed breeds) , or only if absolutely necessary for medical reasons. In the feline realm, these reactions existed but never quite gained the fervor of those in the canine realm.

As if all this weren’t messy enough to foil attempts to introduce reason into the process, the increased marketing of companion animals as symbols of human concerns did what symbolism always does. It made meaningful discussion of spay and neuter extremely difficult if not impossible. People who perceived their dogs symbolically used the words “spay” and “neuter”, but they weren’t talking about what benefited the dog, breed, or species. They were talking about what approach would support their personal beliefs regarding human reproduction and population control. Or abortion and free choice. Or maybe something else entirely. Is it any wonder these conversations weren’t—and aren’t—very productive?

But take heart. Despite the fact that social media may create the illusion that control over the reproductive organs of human and other animals is a contemporary social, moral, cultural, religious, political and/or scientific problem, it isn’t. It’s just today’s variation on an ancient animal theme of other-control that arose in an era when H. sapiens was barely a blip on the Cenozoic horizon.